Born on the Fourth of July

Melinda Blauvelt (American, born 1949), Nellie Mae Rowe, Vinings, Georgia (detail), 1971, printed 2021, gelatin silver print, 21 13/16 × 14 11/16 inches, gift of the artist, 2021.69. © Melinda Blauvelt.

By Katherine Jentleson

Nellie Mae Rowe was born an artist. She arrived the ninth of ten children to her parents, Sam Williams and Louella Swanson Williams, on a very memorable day: July 4, 1900. No existing records confirm her exact birthdate, but the claim she placed on Independence Day at the dawn of a new century reveals the esteem she held for her life and her relationship to freedom.

Rowe’s artistic talent shined from an early age, but she had little time to cultivate it between the farm labor of her youth and the domestic work of her adult years. By 1930, she had left her family’s farm in Fayetteville, Georgia, and moved to Vinings, a city just northwest of Atlanta, with her first husband, Ben Wheat. She remained there after Wheat’s sudden death, marrying Henry Rowe, who made her a widow for a second time in 1948.

For the next twenty years, Rowe lived alone and continued to work for a White family who had employed her in domestic service for decades. Once they, too, were deceased, she proclaimed, “Now I got to get back to my childhood, what you call playing in a playhouse.” In the last decade and a half of her life, she reclaimed her artistic birthright, welcoming visitors to her “Playhouse,” which she decorated with found-object installations, handmade dolls, chewing-gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings.

The exhibition Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe (September 3, 2021–January 9, 2022, High Museum of Art, Atlanta) offers a new look at the many dimensions of her practice and recontextualizes her bold decision not to go quietly into her final years. For Rowe’s choice to practice art was not only a form of self-care but also a way of demanding the respect and visibility that she had so long been denied as a Black woman living in the American South. Though her work rarely directly addressed political or social concerns, it all emerged from a radical act of self-liberation that allowed her to imagine and create a world many degrees more beautiful than the one she knew.

Citation

Jentleson, Katherine. Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, wall text. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, September 3 2021–January 9, 2022. https://link.rowe.high.org/essay/born-on-the-fourth-of-july/.

“Now I got to get back to my childhood, what you call playing in a playhouse.”

-

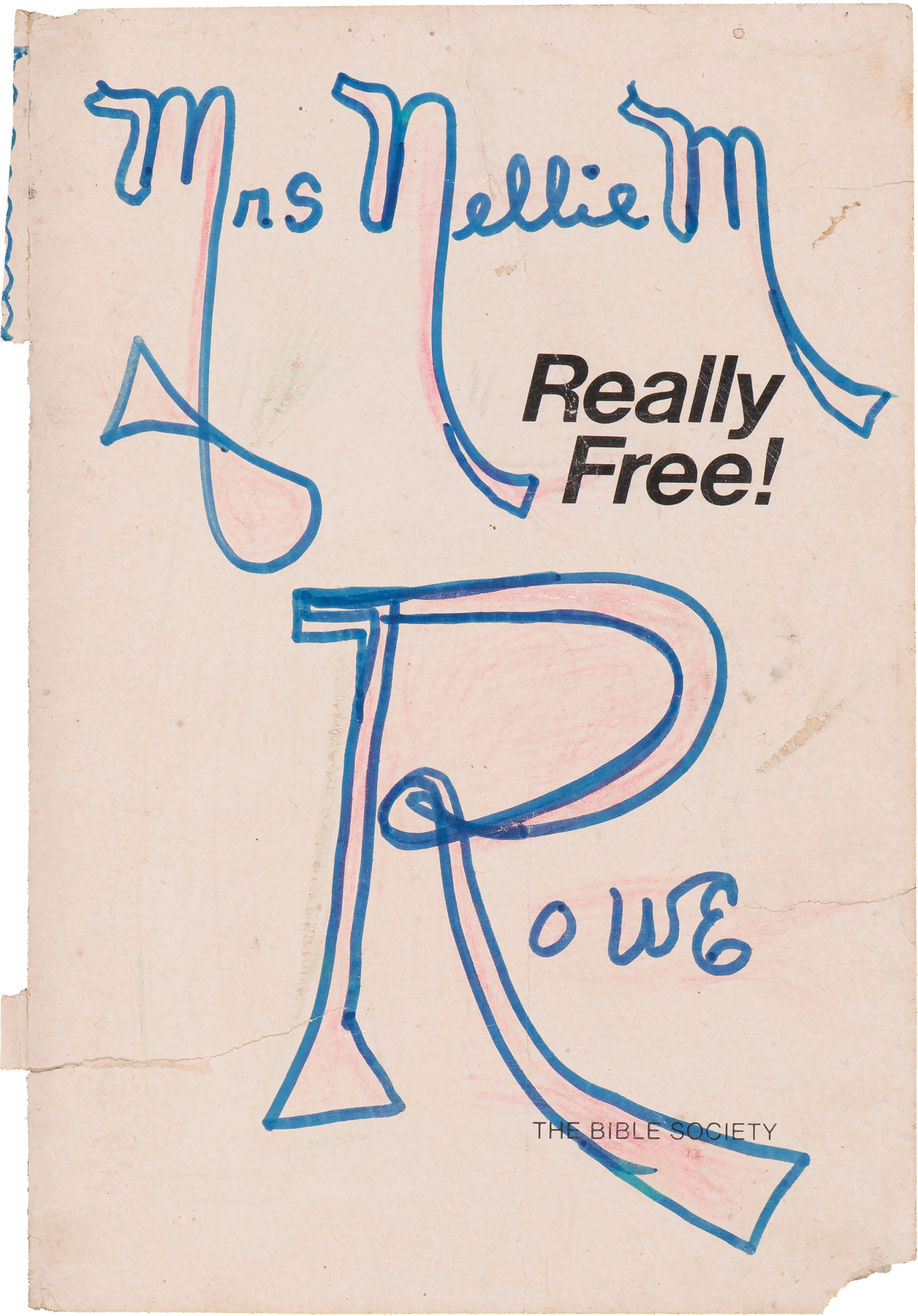

Rowe was a deeply spiritual person who believed that God had bestowed her with artistic abilities, saying, “This the talent that he gave me and I have to use it.” She hung onto the frontispiece of Really Free!, a pamphlet reproducing the Gospel according to John and printed by the Bible Society in 1967, transforming it with her elegant signature. The way that she envelopes the phrase “Really Free!” with her name makes this relatively simple work, which inspired the title of this exhibition, a bold statement about how she expressed her personal freedom through art in the final years of her life.

Untitled (Really Free!)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1967–1976

Marker and crayon on book page

Image/Sight: 7 1/2 x 5 inches (19.1 cm x 12.7 cm) Framed/Mounted: 18 1/4 x 15 1/4 x 1 1/4 inches (46.4 cm x 38.7 cm x 3.2 cm)

Gift of Judith Alexander

2002.239 -

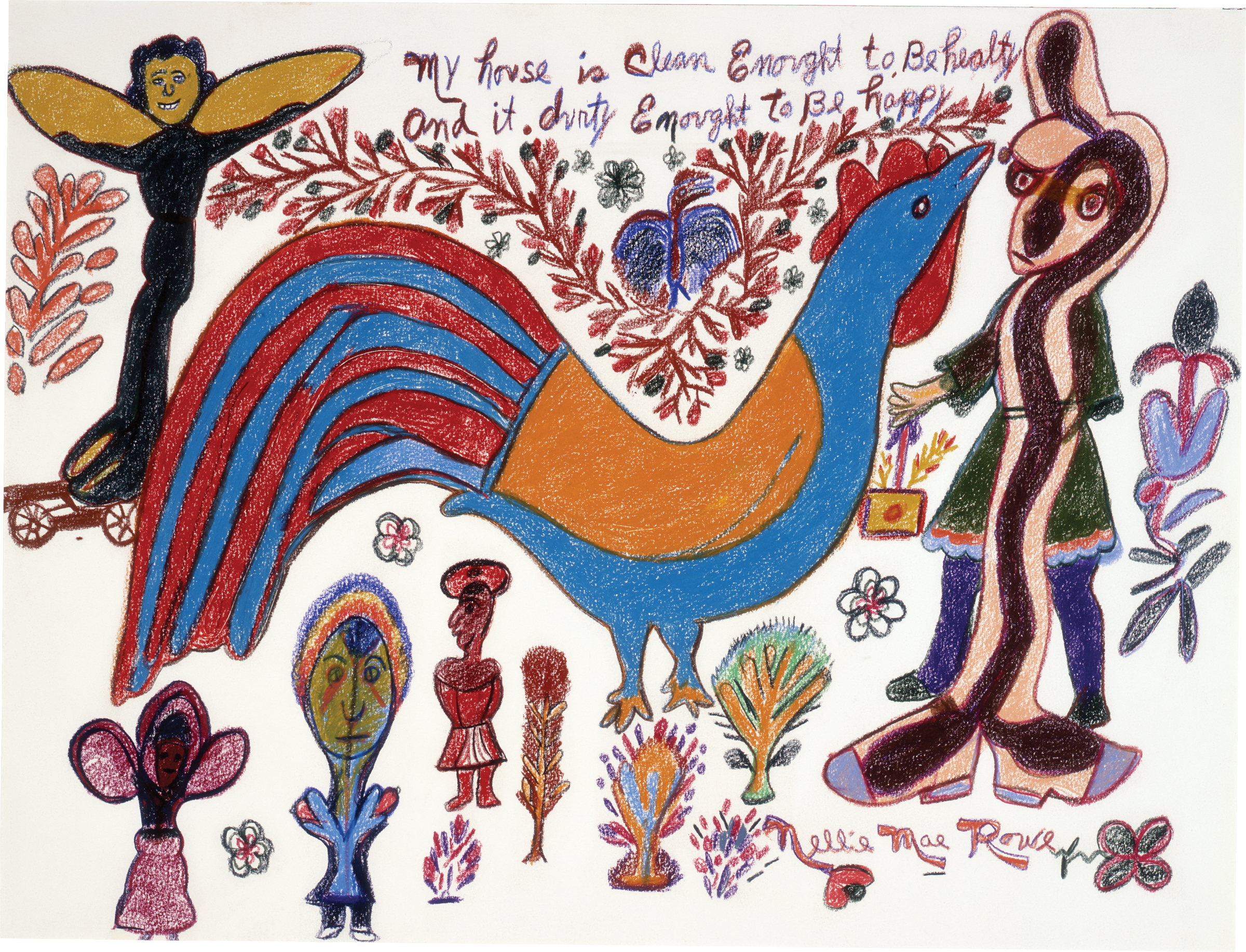

“I kept house long enough, I don’t want to be bothered by nobody ’cept self,” was how Rowe put her decision not to marry for a third time nor to seek further employment as a domestic worker. She got a kick out of household goods that cleverly and joyfully articulated the easing of domestic duties, like a napkin she saw at her niece’s that bore the phrase that is the title of this work.

My house is Clean Enought to Be healty and it dirty Enought to Be happy

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1978–1982

Crayon and pencil on paper

18 x 24 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.146 -

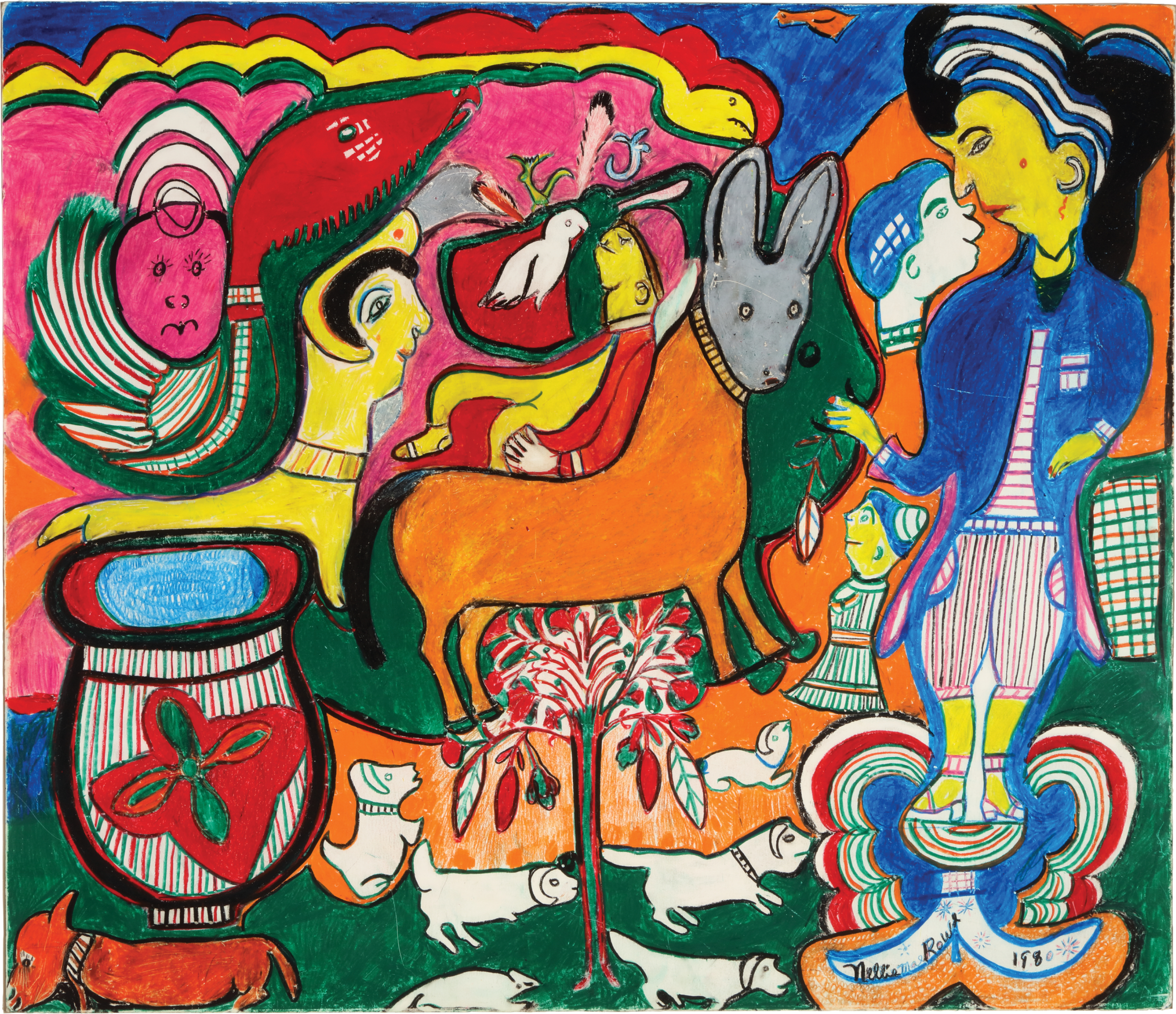

By the time she made this work, Rowe had developed a sophisticated mastery of color and compositional structure. She gained access to very large paper through Judith Alexander, the Atlanta gallerist who began representing Rowe in 1978 and who gave the High the vast majority of its Rowe collection. The dapper blue figure seems to coax the parade of converging dreamlike forms in this drawing, including a sphinxlike yellow creature who follows the central, orange-bodied dog carrying a turban-wearing figure on his back.

Untitled (Orange Dog and Blue-Coated Person)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1980

Crayon and pencil on paper

32 x 36 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.223 -

Wearing green, a signature color in her wardrobe, Rowe rides a chicken toward a form that exemplifies how she married human, plant, and animal life in her work. Its facial features comprise the components of a tree: roots and low limbs form its beard and mustache, while budding branches create its eyes and hair. This peculiar face rests on a neck stacked with Star Trek–reminiscent chevrons, lending it an extraterrestrial air that befits Rowe’s belief in her drawings as emissaries of an unknown future—“things that ain’t been seen” or “something that ain’t been born yet,” as she put it.

Untitled (Nellie Riding Chicken)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1980

Crayon and pencil on paper

18 1/2 x 24 1/2 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.211 -

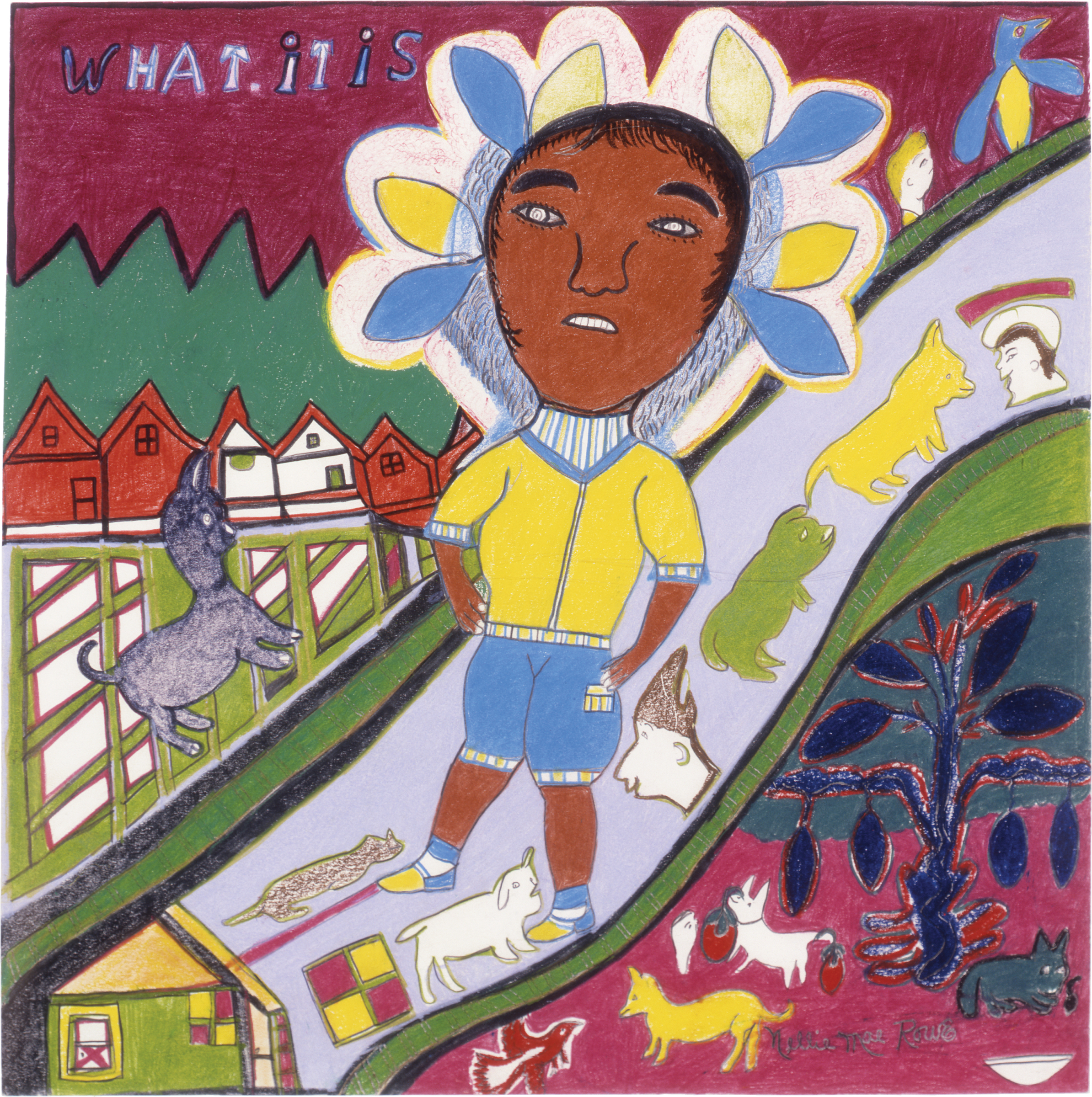

Rowe visualizes herself as a child, confidently walking down Paces Ferry Road, her ribbons forming a kind of halo as she goes. “What it is” is a popular greeting—akin to “What’s up?”—but Rowe also used it as an artistic statement that reflected the mysteries she was content to let remain unsolved in her work. “Most of the things that I draw, I don’t know what they are by name. People say, ‘Nellie, what is that?’ I say I don’t know, it is what it is. That is all I know. But I know one thing, I draw what is in my mind.”

What it is

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1978–1982

Crayon, colored pencil, and pencil on paper

21 x 21 1/4 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.215 -

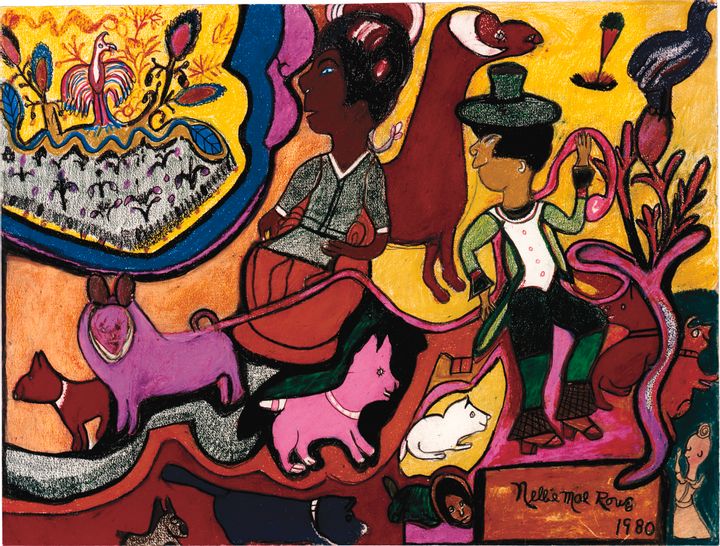

Rowe depicts herself seated in a red chair with her nephew, Joe Brown Sr., who was the son of her older sister Minerva. Rowe settled in Vinings after Brown had begun to make a life there, and when her first husband died, she stayed with Brown and his family until she remarried. She pays tribute to their lifelong friendship through the warm colors of this work, which reflect the glow of a setting sun. A glimpse of heaven emanates from the western corner of the sky, beckoning with its flowering field and rising phoenix, a symbol of spiritual rebirth.

Untitled (Nellie Mae and Joe Looking into Heaven)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1980

Crayon, colored pencil, and pencil on paper

18 x 24 inches

Bequest of Dr. Margaret Sommerville and Jim Sommerville

2006.145