The Playhouse

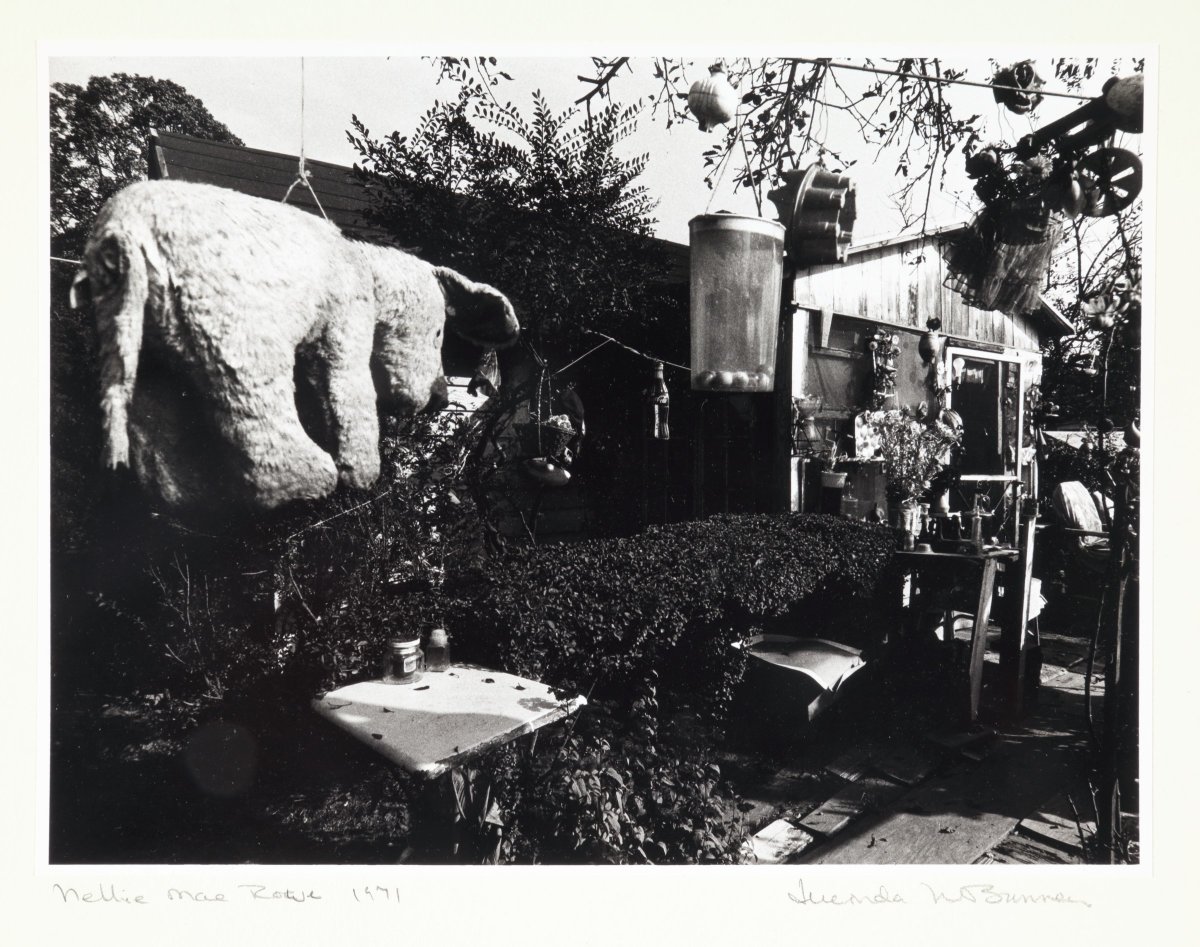

Lucinda Bunnen (American, born 1930), Nellie Mae Rowe’s House, 1971, chromogenic print, collection of the artist. © Lucinda Bunnen.

By Katherine Jentleson

At the same time Rowe revived her drawing practice, she transformed her home and property on the busy thoroughfare of Paces Ferry Road into her Playhouse, creating what one writer for the Atlanta Daily World called “a complete artistic explosion.” Rowe filled pots and urns with plants, embellishing live ones with strands of artificial blooms, and strung garlands and clotheslines from tree branches, hanging them with Christmas ornaments, children’s toys, plastic fruit, and other items. Small pots lined the rails and posts of her fence, and until they became victims of vandalization, her handmade dolls occupied some of the many chairs placed throughout her yard.

The Playhouse was an everchanging work of art that also served as Rowe’s home and a place for social interaction with many curious visitors. “People started coming here taking pictures. [. . .] the traffic would be held up from the railroad clear up to here,” she remembered.

Art environments gained increasing respect from the art world and mainstream media as artworks worthy of documentation and preservation during Rowe’s lifetime, although her Playhouse was demolished not long after her death. Its legacy lives on here in her drawings of it as well as in pictures taken by photographers who visited her there beginning in the early 1970s. Those photographs also became source material for the filmmakers who have recreated the Playhouse as sets for their forthcoming film on Rowe.

Citation

Jentleson, Katherine. Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, wall text. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, September 3 2021–January 9, 2022. https://link.rowe.high.org/essay/the-playhouse/.

“People started coming here taking pictures. [. . .] the traffic would be held up from the railroad clear up to here.”

-

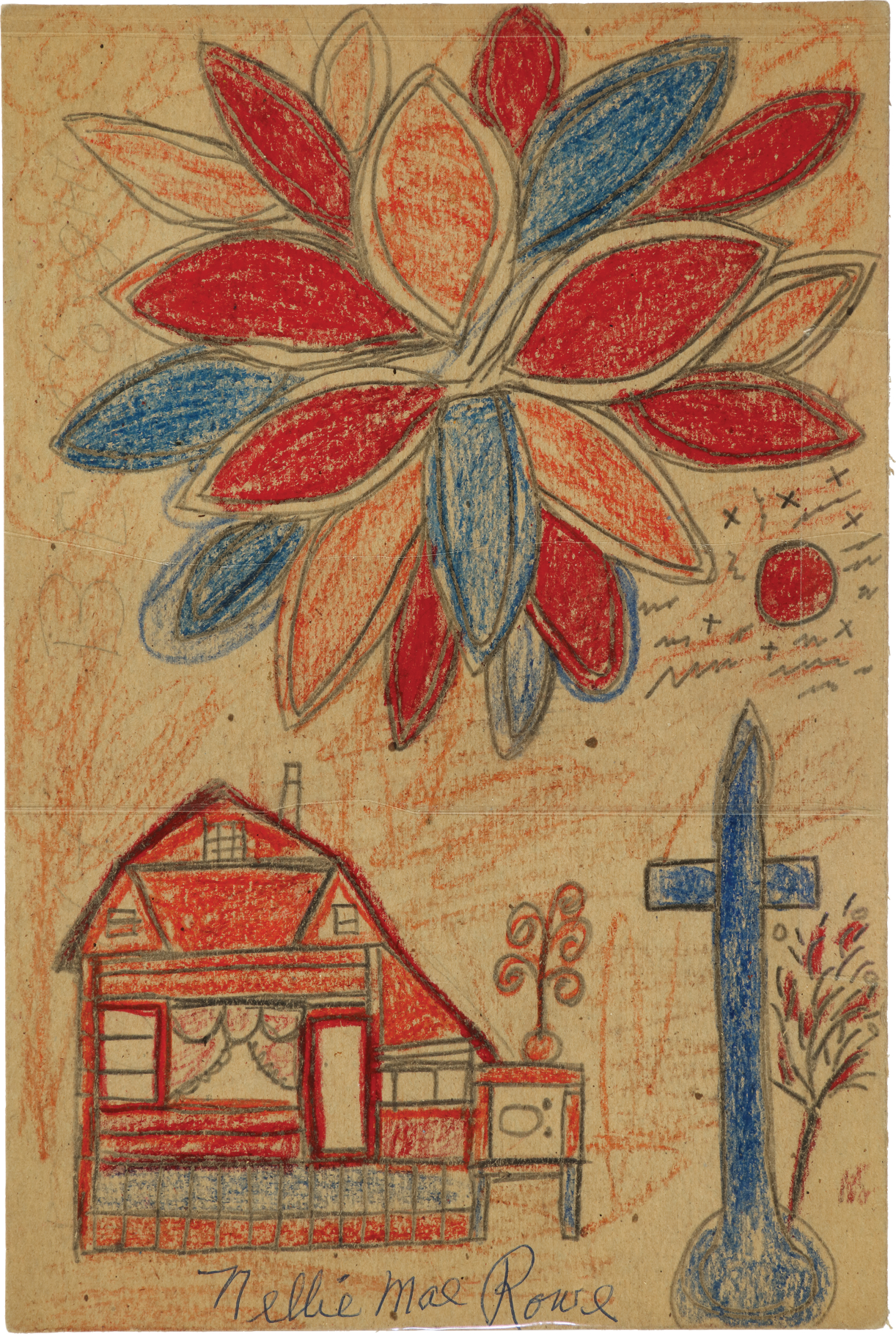

The population of Vinings was in the hundreds when Rowe moved to it around 1930, following her nephew Joe Brown Sr., who had already relocated there. They were part of a small settlement of Black families that relied on a segregated school, two churches, and a cemetery. Her second husband, Henry Rowe, is buried in that cemetery, which was just up a hill from her home. In this early drawing of her Playhouse, she celebrates the cemetery’s proximity and holy presence through the crucifix and radiating floral form in the sky.

Untitled (Playhouse and Cross)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

before 1978

Crayon and pencil on cardboard

13 x 9 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.207 -

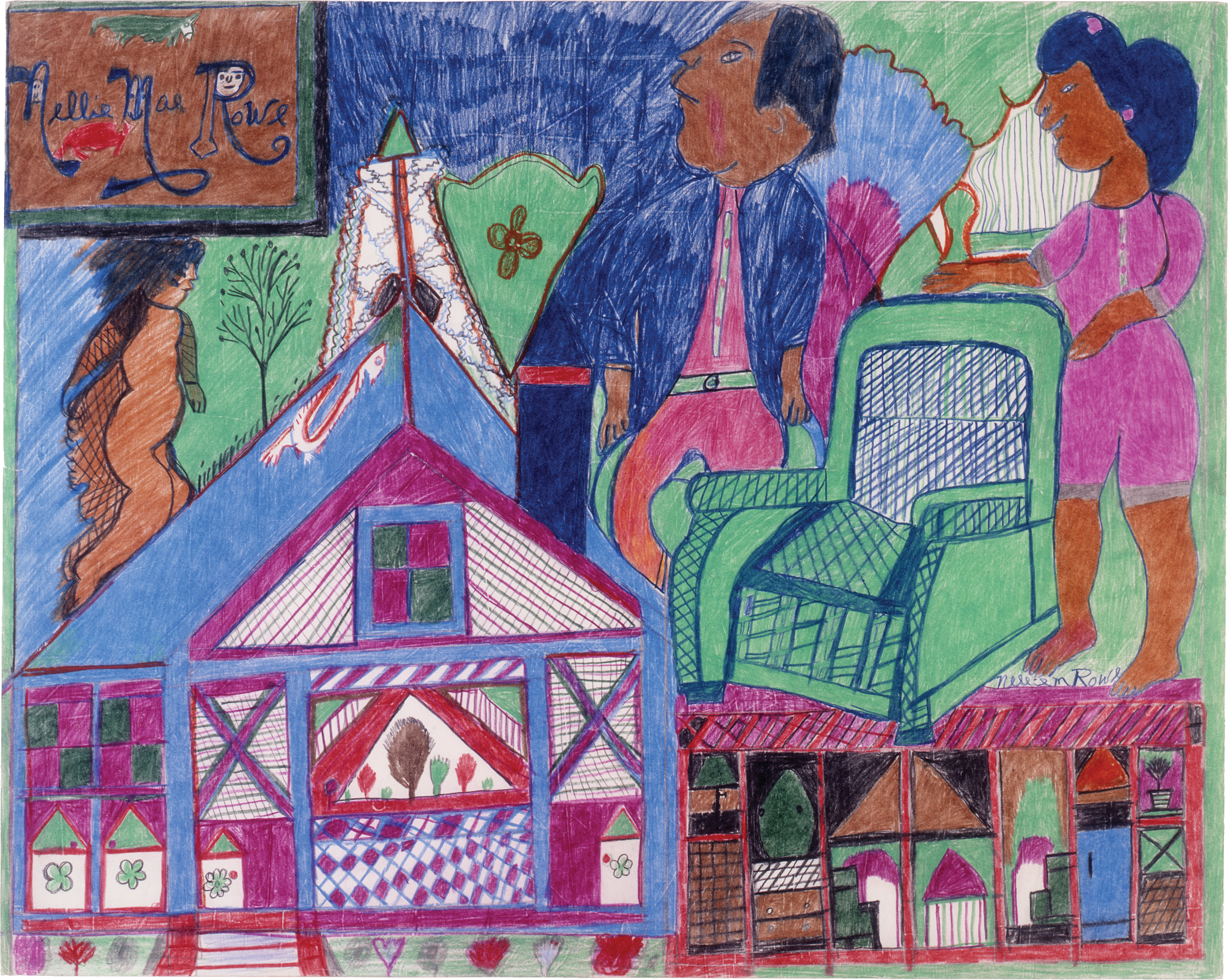

Rowe offers her late husband Henry Rowe a seat as he looks up into a clear blue sky, about to make his transition to heaven. Her inclusion of the Playhouse both honors their lives in the home they built together and also foretells how she would transform it into the stage for her artistic renaissance. Although Rowe mourned her husband, she was also relieved to be free from domestic duties. As she told one interviewer quite bluntly, “My husband died in’48 and I ain’t been bothered with marrying or cooking since then—whew, child, I couldn’t stand it.”

Untitled (Nellie and Henry)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1978–1982

Crayon, colored pencil, and pencil on paper

19 x 23 1/2 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2002.244 -

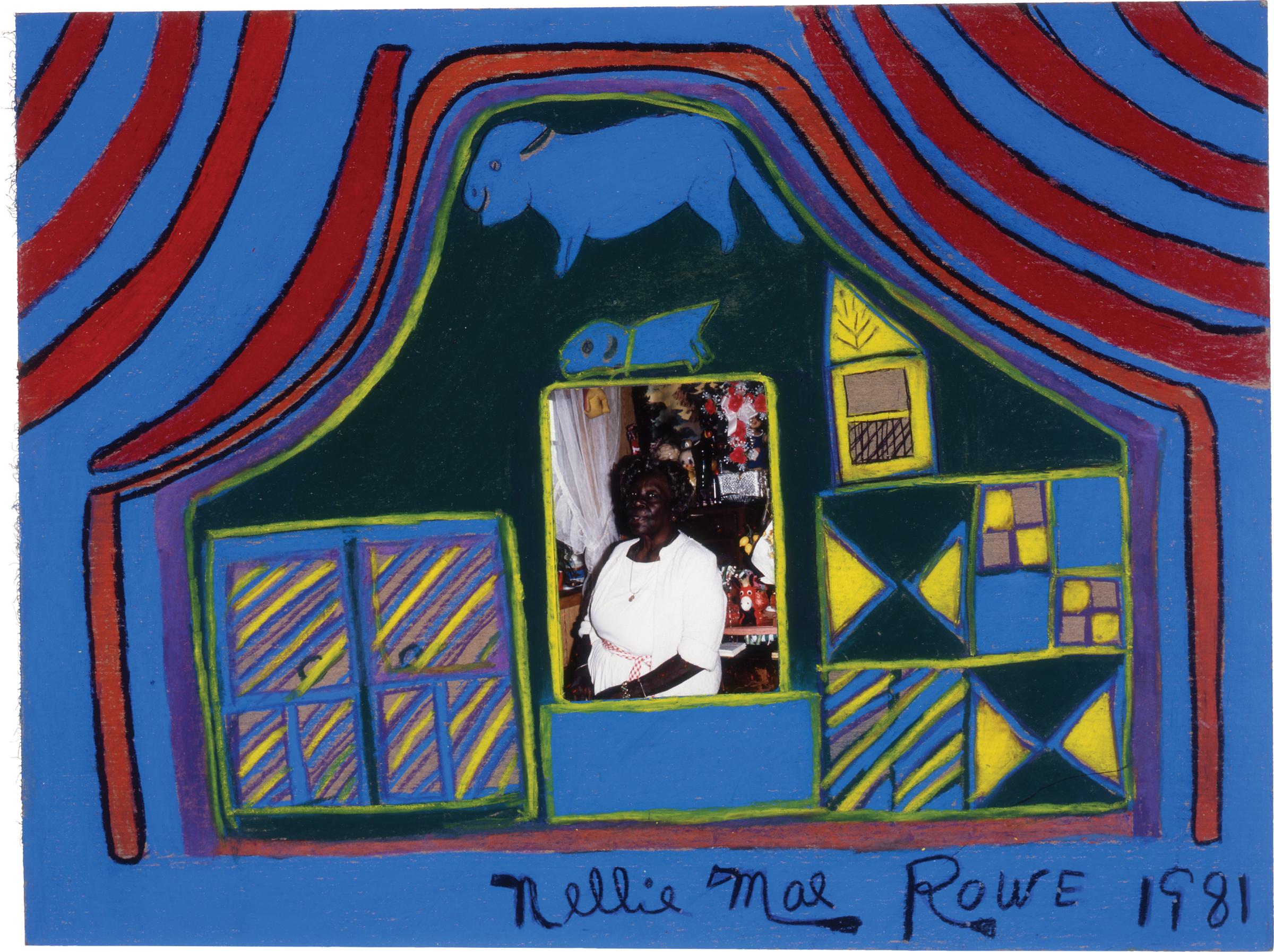

While Rowe was making her Playhouse, art environments attracted attention from scholars studying the African diaspora. Rowe’s use of “haint” blue on the exterior of her home, which she depicts here in a richer indigo tone, was among the practices that were thought to show the retention of African traditions. The Congolese belief that evil spirits, which became known in the American South as “haints,” could not cross sky or water is thought to have been the source of the many exteriors, roofs, and thresholds painted blue throughout the region.

Untitled (Nellie Sitting by the Window)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1981

Color photograph, crayon, and pencil on board

14 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2003.143 -

A connection to nature dominated Rowe’s childhood, as the type of task she was assigned on the farm was dictated by seasons and weather. She reclaimed that connection by tending to the garden of her Playhouse, which was filled with flowering plants like the mulberry tree that she enjoys in this drawing. After 1969, the completion of I-285 drastically changed her surroundings. The space that she made for nature to grow densely, as seen in the photograph by Melinda Blauvelt, was all the more meaningful against the backdrop of the rapidly gentrifying suburb where she lived.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Vinings, Georgia

Melinda Blauvelt, American, born 1949

1971, printed 2021

Gelatin silver print

Framed/Mounted: 23 1/4 x 29 1/4 x 1 1/4 inches (59.1 cm x 74.3 cm x 3.2 cm) Image/Sight: 21 3/4 x 14 5/8 inches (55.2 cm x 37.1 cm)

Gift of the artist

2021.70 -

Untitled (Nellie in Her Garden)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1978–1982

Crayon and pencil on paper

27 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander in honor of Marianne Lambert

2003.173 -

Dogs appear frequently in Rowe’s drawings and are often interpreted symbolically, most commonly as an alter ego or a kind of spirit animal. Rowe did not own dogs, but she used stuffed animals and other novelty dogs frequently in her installations at the Playhouse. The blue dog in Happy Days is particularly reminiscent of a toy dog she hung from a tree that was captured by photographer Lucinda Bunnen.

Happy Days

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1981

Crayon and pencil on paper

18 x 24 inches

T. Marshall Hahn Collection

1997.105 -

Untitled (Blue Dog with Red Collar)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1978

Crayon and pencil on paper

11 x 7 3/4 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

1998.97 -

Untitled (Nellie Mae Rowe Playhouse with Dog)

Lucinda Bunnen, American, born 1930

1970s

Gelatin silver print

6 5/8 x 9 inches

Promised gift of Lucinda Bunnen

PA.FOL.NMR10 -

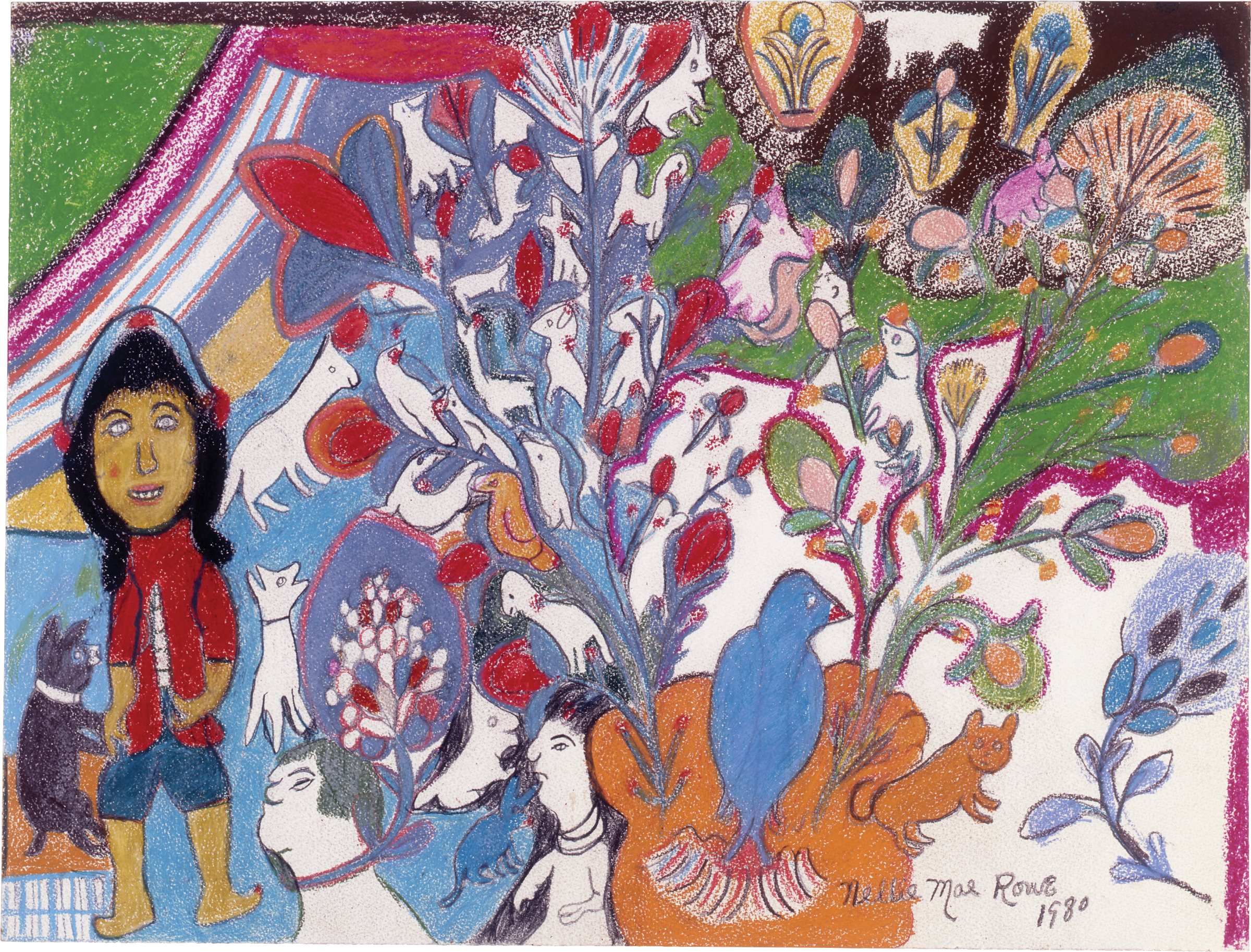

The ornamented tree in this drawing corresponds visually to the one seen in this photograph by Melinda Blauvelt, showing how Rowe’s imagination fed both her drawings and her built environment, and the two practices also cross-pollinated each other. Rowe’s aesthetic of fullness reigned in both space and on paper. The abundance of color and form in drawings like this one reflect the chockablock nature of the Playhouse, which was teeming with its own characters, patterns, and vignettes.

Untitled (Girl in Red Vest)

Nellie Mae Rowe, American, 1900–1982

1980

Crayon and pencil on paper

18 x 24 inches

Gift of Judith Alexander

2002.248 -

Nellie Mae Rowe’s Yard, Vinings, Georgia

Melinda Blauvelt, American, born 1949

1971, printed 2021

Gelatin silver print

Framed/Mounted: 23 1/4 x 29 1/4 x 1 1/4 inches (59.1 cm x 74.3 cm x 3.2 cm) Image/Sight: 14 5/8 x 21 3/4 inches (37.1 cm x 55.2 cm)

Gift of the artist

2021.68 -

In this stunning portrait, Melinda Blauvelt captured the extraordinary air that Rowe seemed to carry with her at the Playhouse. Rowe pressed bottle caps into the ground, creating the effect of shiny penny tile near the threshold of her gate, which she wove with old straps and cords, a tribute, perhaps, to her father, who was a talented basket maker. Blauvelt was among the first photographers to make Rowe her subject, and her portraits were used in the groundbreaking 1982 exhibition Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980, discussed toward the end of the exhibition.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Vinings, Georgia

Melinda Blauvelt, American, born 1949

1971, printed 2021

Gelatin silver print

Framed/Mounted: 29 1/4 x 23 1/4 x 1 1/4 inches (74.3 cm x 59.1 cm x 3.2 cm) Image/Sight: 21 3/4 x 14 5/8 inches (55.2 cm x 37.1 cm)

Gift of the artist

2021.69

Reimagining Rowe’s Playhouse

These images depict models of Rowe’s Playhouse that were created for This World is Not My Own, a hybrid documentary about Rowe’s life that will make its worldwide debut in 2022. Very little footage capturing Rowe or her Playhouse exists, so the filmmakers of Opendox were inspired by the more abundant photographs of the Playhouse to create this miniature model of her home and yard, as well as a larger reimagining of the interiors of her home, both of which are included in the exhibition.

Rowe’s insistence on playing and her creativity with everyday materials inspired the details of these sets, which include a tree made of popcorn, stepping-stones from wine corks, a table sitting on marker caps, and other whimsical items. Ruchi Mital, one of the filmmakers behind This World is Not My Own, writes about their approach to reimagining the Playhouse in the exhibition’s catalogue.